How can organizations have an efficient and streamlined process to get budget allocated and expenses approved, giving every employee autonomy and flexibility to do their best while maintaining a high degree of accountability and auditing?

Getting expenses approved in medium or large organizations is usually a cumbersome and bureaucratic process. There are different policies for each type of expense, such as training, project-related expenses, hardware purchases or team-building activities.

We believe lean organizations can be more adaptive and efficient by providing autonomy and agility to their coworkers while keeping a high degree of accountability and auditing. Distributing and automating the decision-making process of allocating budget and approving expenses while maintaining a high level of control and accountability is possible.

That is what we started doing three years ago, and it has been working great for us. Companies undergoing a digital transformation process could cut costs, reduce overhead, and increase employee engagement with an approach like this.

For a while, we had a few internal budgets that coworkers at Manas could use for different purposes, such as personal activities, training and conferences, events, and hardware. However, in 2016, we started exploring a more streamlined and unified system that could be used to approve any expense required.

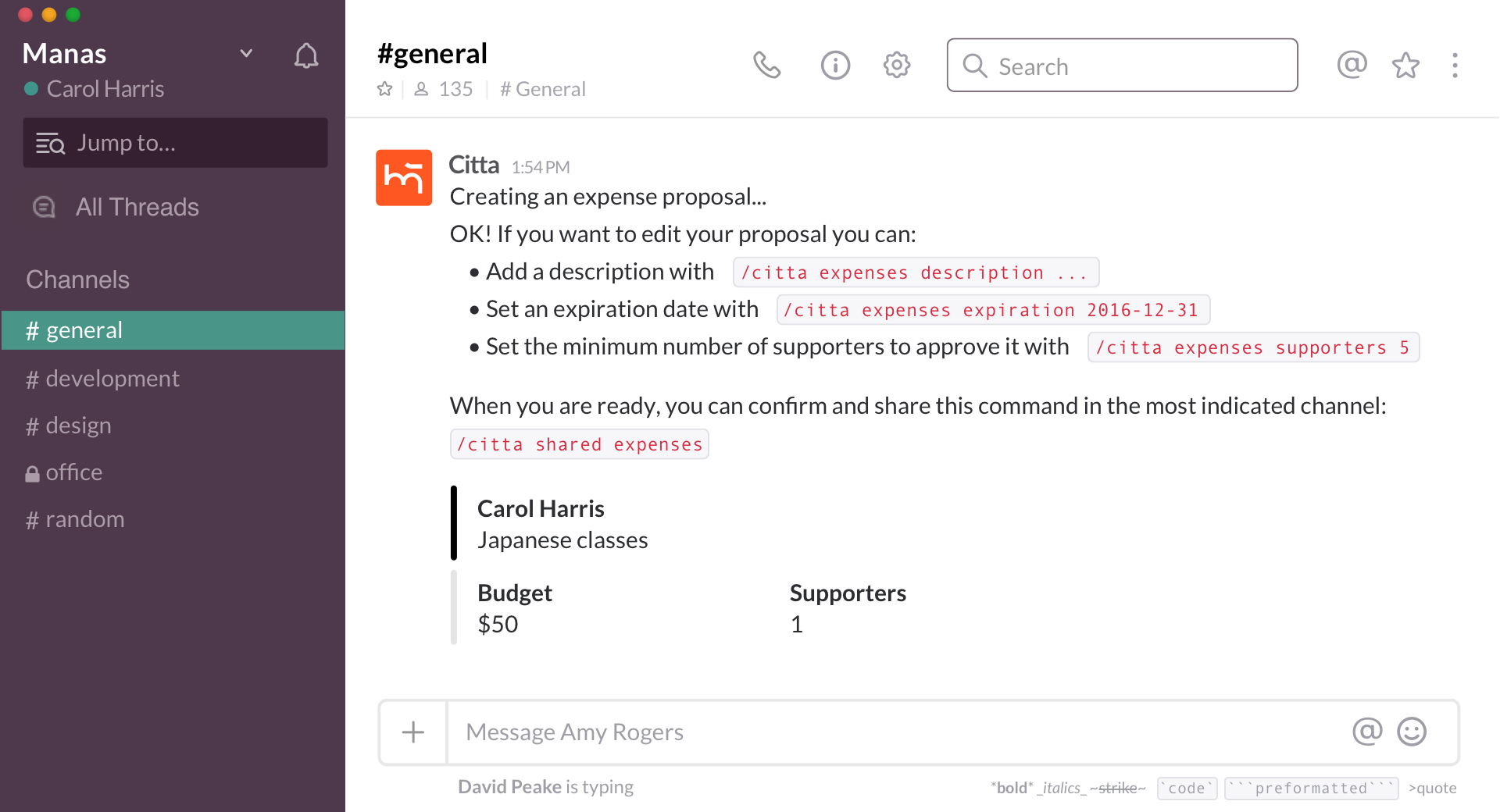

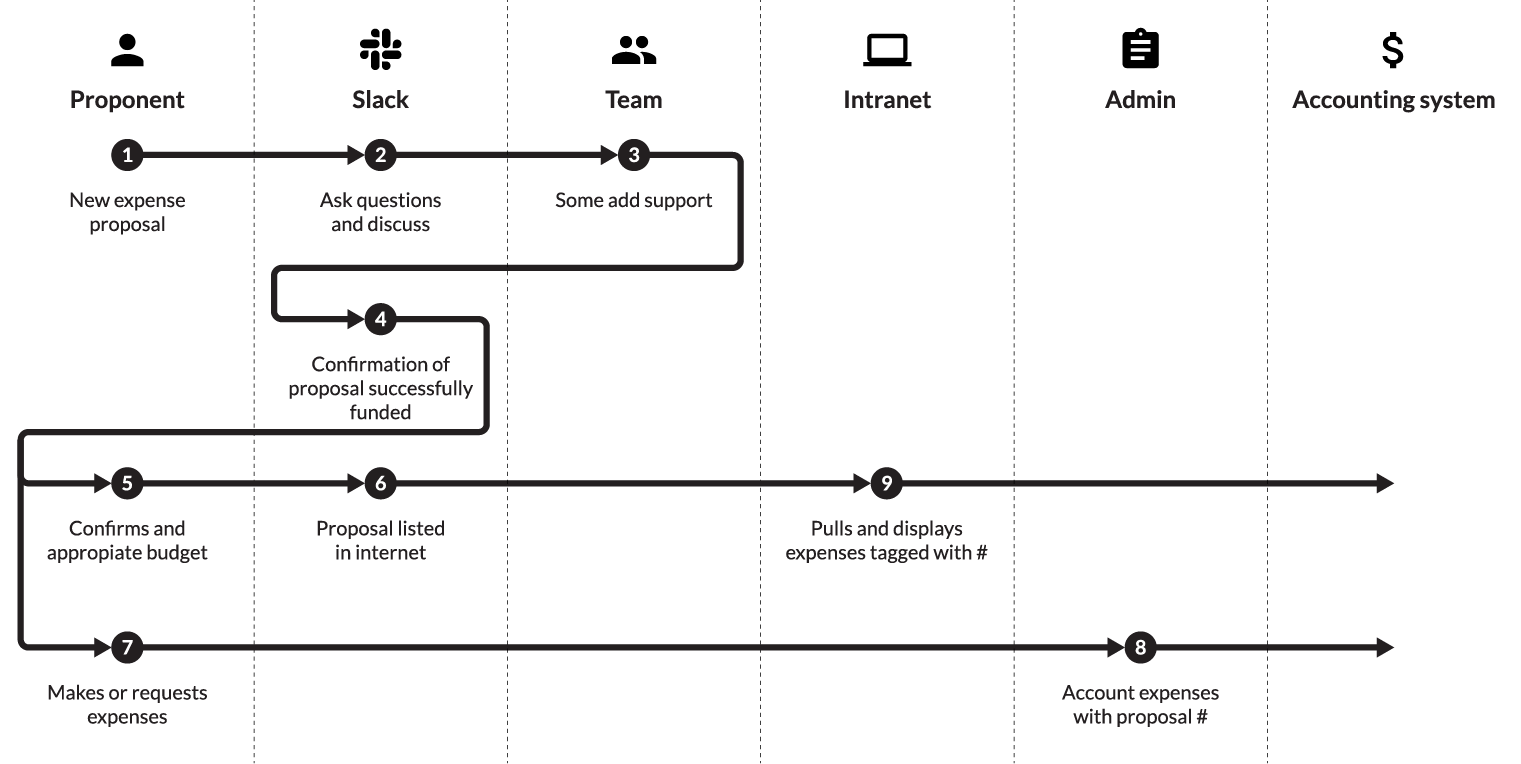

The basic idea is simple: anybody can propose an expense to a group of people in the organization (we do it via a Slack channel) and get almost immediate approval on it. The larger the amount is, the more people that are typically needed to get it approved.

Design goals

- Decentralize decision-making on expense approval: nobody likes (or at least nobody should like!) to spend time reviewing and approving individual expense proposals. Not only does that create a bottleneck, but it also happens that the person in charge of review and approval is usually not knowledgeable about what’s needed.

- Avoid policies: nobody likes to have to consult a policy manual to decide if an expense is appropriate or not. Plus policies get outdated soon and can’t cope with new situations that were not foreseen.

- Autonomy: we hire adults and we treat them like that, if a person needs to buy a book, software, or take Japanese classes, we want them to have the freedom and autonomy to make the call.

- Increase the individual budget with seniority: the longer a person has been in the organization, the larger the expenses they should be able to command without peer-approval.

- Create shared responsibility on budget allocation: for more significant expenses, we want more team members to take part in the approval decision.

- Have a transparent and auditable expensing system: we wanted all variable expenses to be visible, tracked and accounted against the proposal that approved them.

How it works

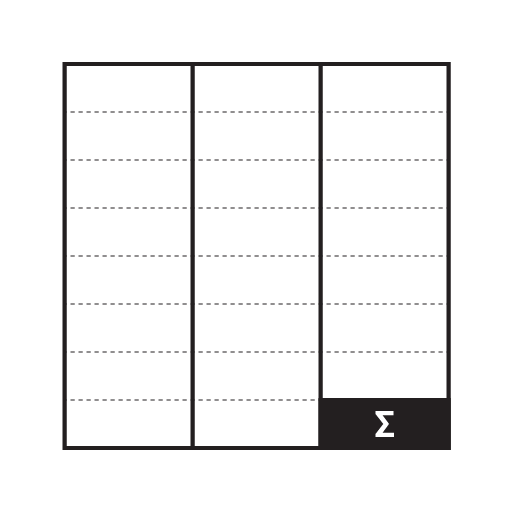

- Every four months, we determine the budget available for the next period. That is the total budget for all variable expenses.

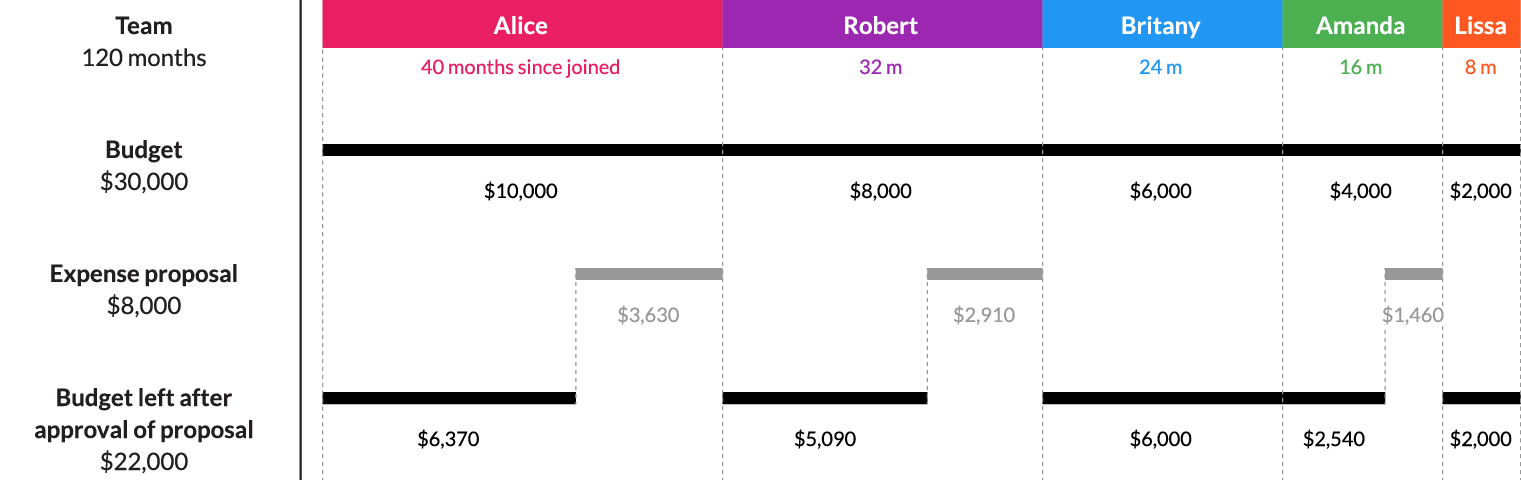

- Every person has control over the allocation of a fraction of that budget. The fraction each one can allocate is proportional to the total months they have been part of the organization. This is done to ensure a progressive alignment with the culture and mutual trust to be developed before significant expenses can be approved individually.

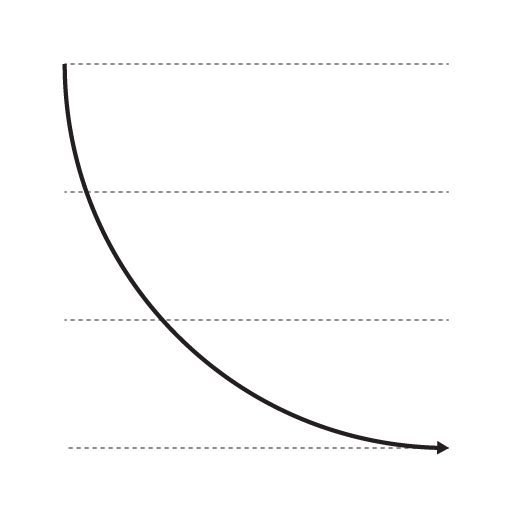

- There is no limit on the expense amount that anybody can propose, but the more significant the expense, the more cumulative seniority months required to approve it.

- All expense proposals are visible internally.

- Interested people can support the proposal.

- Once enough support to fund the proposal is obtained, the proponent can approve the proposal.

- Budget is deducted proportionally from the people that supported an expense proposal.

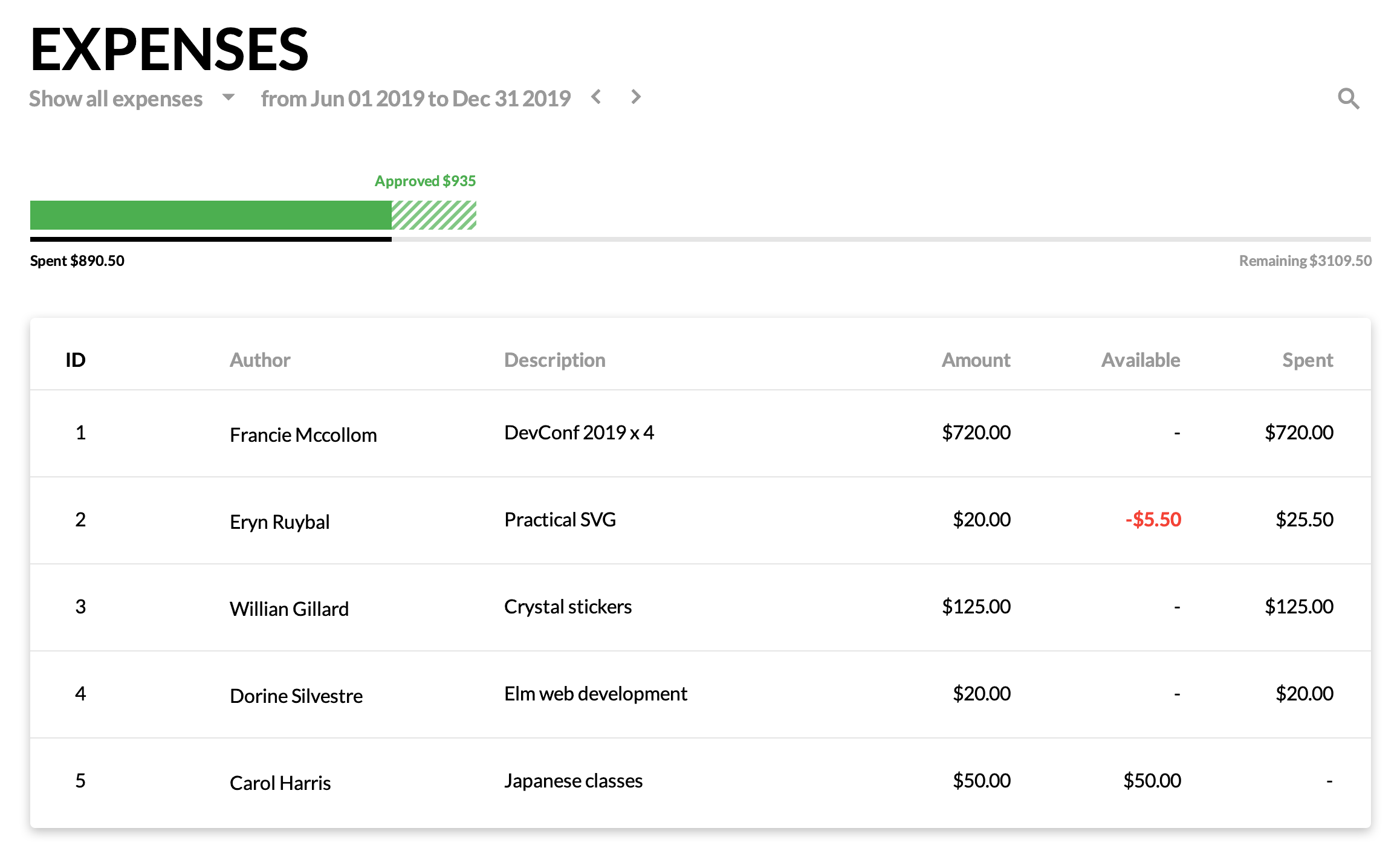

- The system is connected to our accounting software, pulls actual expenses, and matches them against their proposals, showing the details of how the money was spent.

- The system also displays all variable expenses that don’t match against any proposal and displays those as deductions to the available budget. When those with company credit-cards forget to make a proposal, or there was a contingency, this ensures accountability. While these people can still spend money without going through the process, that is transparently communicated and accounted.

Why it works

Bottom-up initiation

Needs are typically discovered at the individual level or in small teams, by people working on the core of the business. The described system empowers anybody detecting a need for their work, professional development, or personal needs, to channel that to an expense proposal.

For small expenses, the risk of buying the wrong thing or stepping out of the organization’s cultural norm has a negligible impact; we could call those discretionary expenses and be done with it.

For more considerable expenses, the system guarantees that either a large number of people have reviewed the proposal and agree with it, or that people with a long time in the organization approve of it. Any blend of those things guarantees cultural alignment.

Incremental budget prioritization

The budget any organization has available over a business period is limited. A typical annual budget process will prioritize all needs at a point in time, and allocate budget accordingly. However, that leaves no room for adapting to changing needs.

With this system, as time progresses and more budget gets allocated, it becomes increasingly harder to get expenses approved. That means that proponents of expenses need either a broader base of support or the support of more senior members of the team. That ensures that we prioritize with more scrutiny as we have lower reserves on the budget. It functions as reverse earmarking for essential expenses that arose late in the period.

Complete transparency

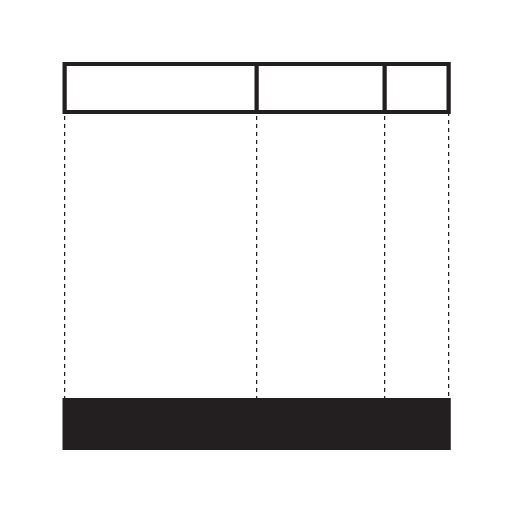

Expense proposals start as a custom message in Slack. That enables a conversation when needed. People support a proposal by clicking a button on the message, and that updates the number of supporters displayed.

All expense proposals are visible internally and linked to the message in Slack that initiated it. When anybody needs to spend money on an approved proposal, they refer to the admin team the proposal id. The admin team tags the bills on our accounting system with the expense id. Those expenses get automatically pulled in the proposal listing so we can all see how that money was spent.

Making organizational information open for self-regulation, learning and mutual support is key to foster innovation and adaptation.

Fostering cooperation

It would be easier to ask people to vote if they like or not an expense proposal. But that creates a false model where there is no limit to what we can like or ask for. When people are forced to confront the allocation of a limited budget, decisions get aligned with the real-world model instead of a “sure, why not” mentality.

The internal mathematical model is such that budget is leveraged by gaining support from other: i.e. each person has more budget accessible when supporting somebody else’s proposal than when funding your own. This, coupled with the repeating nature of the process, counteracts some of the pitfalls with the public goods dilemma.

Top-down assumption checking

When expense decisions are made top-down, we run the risk of having wrong assumptions of what is needed or desired. We recently had a situation where our People and Culture Lead wanted to provide free-meals to the team via a daily delivery service with good options, but the expense proposal did not gather enough support. We had to conclude that people didn’t want or need that.

This model allows leaders to check if a company-wide benefit or initiative has meaningful support from the organization, addressing inefficiencies that arise from what’s known as the multiple principal problem.

Appendix #1 - How could this scale?

Having everybody exposed to the day-to-day expense decisions in a large company doesn’t scale. The same model can be applied by partitioning a company in smaller groups and “federating” each group at a higher level.

Let’s explore this with an example:

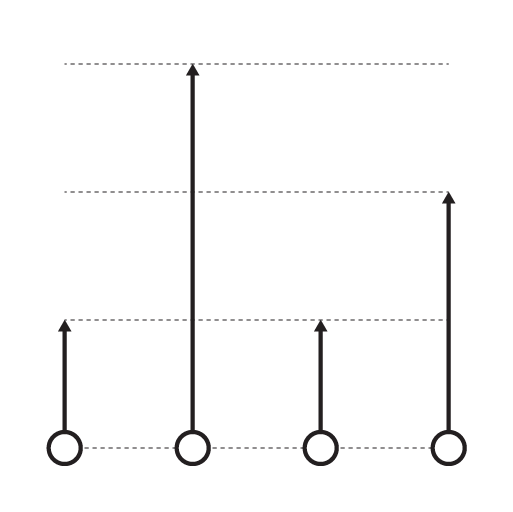

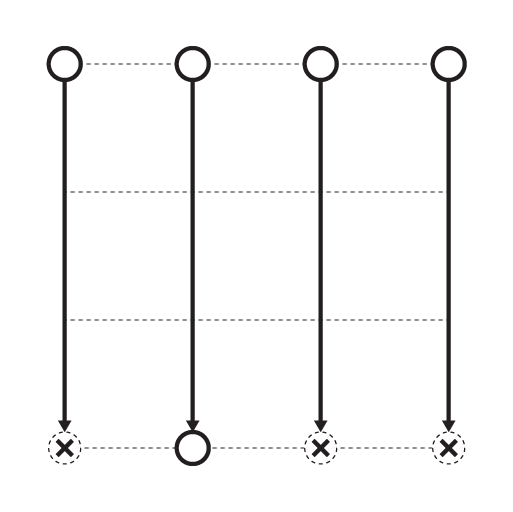

[organizational tree with 3 levels: executive team, areas, individuals at each area]

Each period, the executive team (maybe consulting with the board) decides the budget available. Each area VP then behaves as a participant in that budget (together with the CxOs), appropriating parts of it by proposing budget allocations. Things like “R&D for the first quarter” or “Team perks for the year.” CxOs and VPs then provide support or not for those proposals following the same rule: a VP that just joined a month ago, will need a higher oversight of their peers to get the budget approved.

Then the process repeats at the lower layer by making the approved area budget available to the area team. At that level, the team then breaks down the allocation by proposing more granular budget allocations.