A couple of weeks ago, Nico sat down with the whole Manas team, and presented the model he had been working on for the past few months: the Career Garden.

So, what exactly is a Career Garden?

It’s a kind of multidimensional distribution of roles and responsibilities within an organization, rather than the traditionally vertical hierarchies, or the new sprout of horizontal approaches -that end up being, one way or another, still very much unidimensional. But also, it’s a profound statement about who we are, our culture, and how we do things. Allow me to explain.

About a year ago, it came up that there were some reviews on openqube.io, in which people mentioned that a downside of working at Manas was the lack of a formal organizational structure.

“The horizontal organization leaves some things up to who speaks up the most. And the career path it’s not clear after a few years of being in there…”

“The other face of horizontality is the lack of a defined career path. It’s key to be proactive and have a push of your own to find how to grow inside the company.”

This was a problem, because it was not a bug, but a design feature. Not having a boss, not having a list of preset tasks that define what your job is, not having a fixed rail along which you move like a wagon, not having your professional future laid out in front of you, set in stone. That was all part of an intentional configuration, meant to give people the freedom and the tools to forge their own growth path.

So, what do we do?

An obvious alternative is to blame it on them. ‘Maybe they’re not the right fit’. Yeah, that sounds about right and it certainly would make us feel good about ourselves. ‘We did everything we could do, but hey, they are simply not ready. Let’s just find some people who are a better fit for us’. With this approach come several problems: first, it can seriously complicate the recruiting process, and perhaps even spiral into a high-rotation syndrome that threatens replicable knowledge and productivity. But that is just from a business perspective. On the cultural end, this approach obliterates morale and creates a scenario with two-sides, divided by an ever growing, un-bridgeable gap: on one side, “the autonomous pathmakers”, and on the other side “the helplessly heteronomous”. The real danger, however, is avoiding introspection. Falling for the belief that we, as an organization, don’t have any kind of implication on the problem.

The other alternative, less obvious, more challenging and demanding, is to try and solve the problem. At least, address it. So that’s what the career garden is. Our shot at solving an important problem.

The base assumption behind our organization model is that the traditional, linear, ascendent, cumulative career path is no longer correspondent with the tenets of reality:

- the average worker stays in their job for less than 5 years, which no one would really consider a ‘career’. This is the general average, the technology industry is well below that (not to sound pretentious, but this is actually not our case, we are averaging a healthy 8 years, with people breaking the 15 year barrier;)

- from one organization to another, structures and hierarchies don’t really correspond, so changing jobs can often mean going back a category or two, or jump forward an unrealistic amount of spaces in the imaginary boardgame of corporate work

- ever since the 80s, when companies started balancing their books by firing people, the average worker no longer dreams of staying in one job for too long, and instead embraces change and growth in other places

- most importantly, the speedy advances of technology and the birth of new types of professions, occupations and careers (who could have imagined being an AirBnB host for a living in early 2008?) create a work dynamic that forces us to rethink what a career actually is, and ponder if it wouldn’t be better to break each of them down into its components, and see if some of those are common to various different roles or careers

In simpler, harsher words, the good ol’ career path our parents told us about is dead yet not buried. So, after burying it once and for all, we realized we had a responsibility to ourselves to sit down and reflect on what that meant, how it affected us and how we were going to build the next model. The career garden is that next model (for us, at least).

However, even after we tackled all these major problems of the industry — all industries, in some cases-, there is no perfect model, and thus we find that our answer breeds new questions, and yes, we feel we must address those as well. The career garden is our attempt at a second row of answers to this second wave of questions.

Some of the goals of the career garden are providing containment to people in the organization and create some sort of scaffolding, a transitional and temporary structure that has the purpose of allowing growth, without acting as its limit. It also brings a higher degree of clarity about roles and responsibilities to the table, and it facilitates scalability, all without losing “horizontality”, fluidity to transition from one role to another, stepping-in and dynamism. A hard task, you might be thinking. And you’d be right. But hey, it’s what we do best.

What does it look like and how does it work?

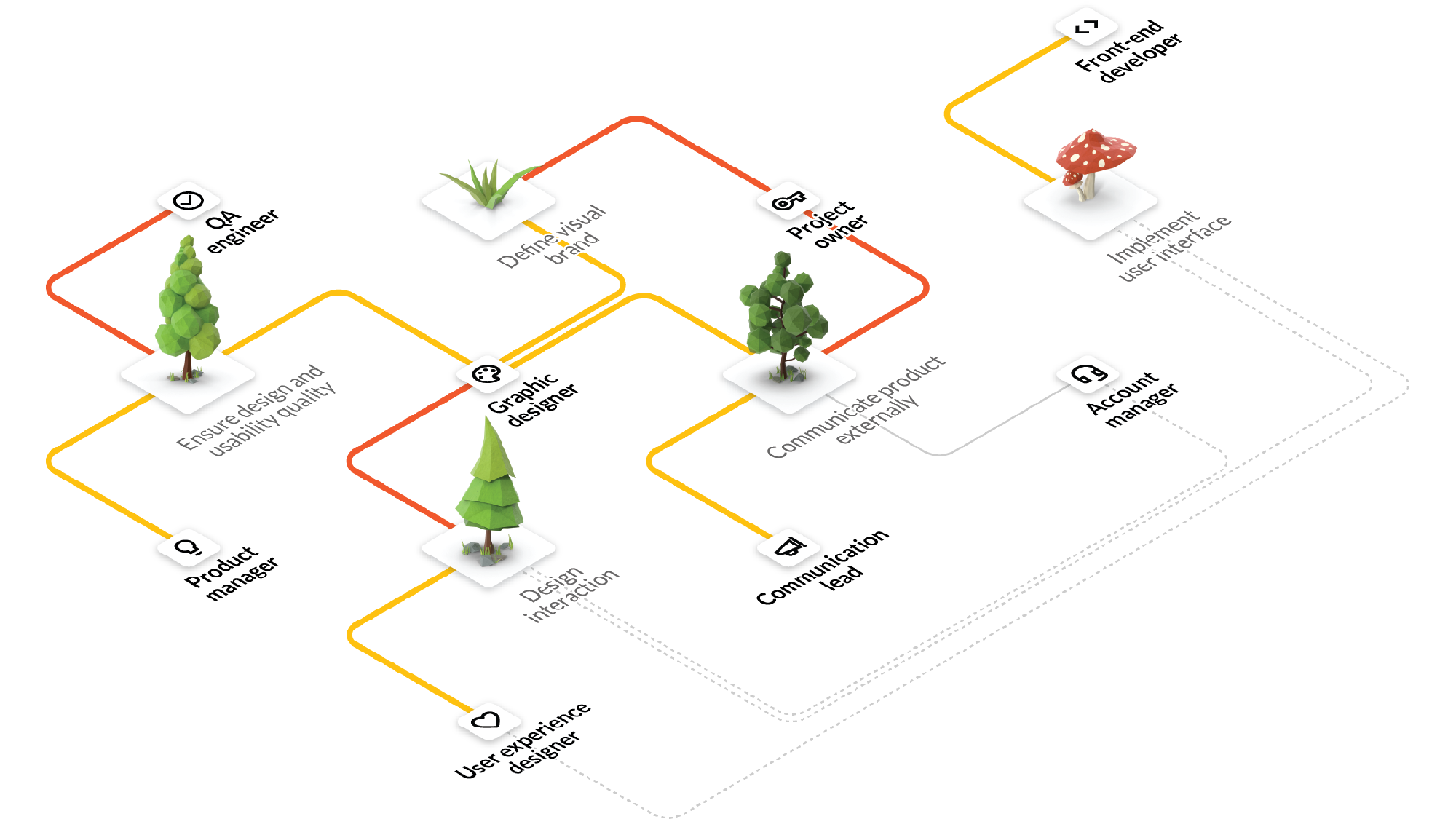

The visualization can be complex because, after all, the model is supposed to reflect a complex reality. So starting with the basics: let’s imagine a garden.

In this garden, we find various different plant species, each representing an area of responsibility. We also find, of course, gardeners, who are in charge of looking after every species in the garden. Now, in no way you could say that a gardener that looks after a tomato plant is ‘better’ or ‘worse’ than a gardener that looks after a basil plant, or another one who tends to a lemon tree. They are simply different. Also, each species is different from the next, has different needs and characteristics, and thus it would be unreasonable to expect that they require the same from their surroundings and from the gardeners. Each gardener, in turn, is different from everyone else in their approach to caring for plants and trees. And, since some species require an amount of time and effort that allows for one gardener to look after it while taking care of others, but some species are more demanding and require full time dedication, it is very unusual to find two gardeners who can be considered identical in their abilities and responsibilities.

So, stemming from that analogy (pun very much intended), one sees that, in a garden, there is room for many different crossings: leaves and branches can grow to the point of intertwining, which can also occur under ground, at the roots level, and also the gardeners tending to the garden often cross paths in their comings and goings. Also, some species require more than one gardener to look after it, so collaboration is a feature by design. Most importantly, while a (corporate) ladder is a single-player endeavor, a garden is an ecosystem, and every element is connected to, and depends on, every other element.

If all of this sounds like it could be said about the people in any organization, that is because that’s how the garden analogy came to be: we believe that no role in an organization can be said to be ‘better’ or ‘worse’ than any other, that different people have different needs, just like different roles entail different responsibilities, and it would certainly be unreasonable to expect the same from everyone.

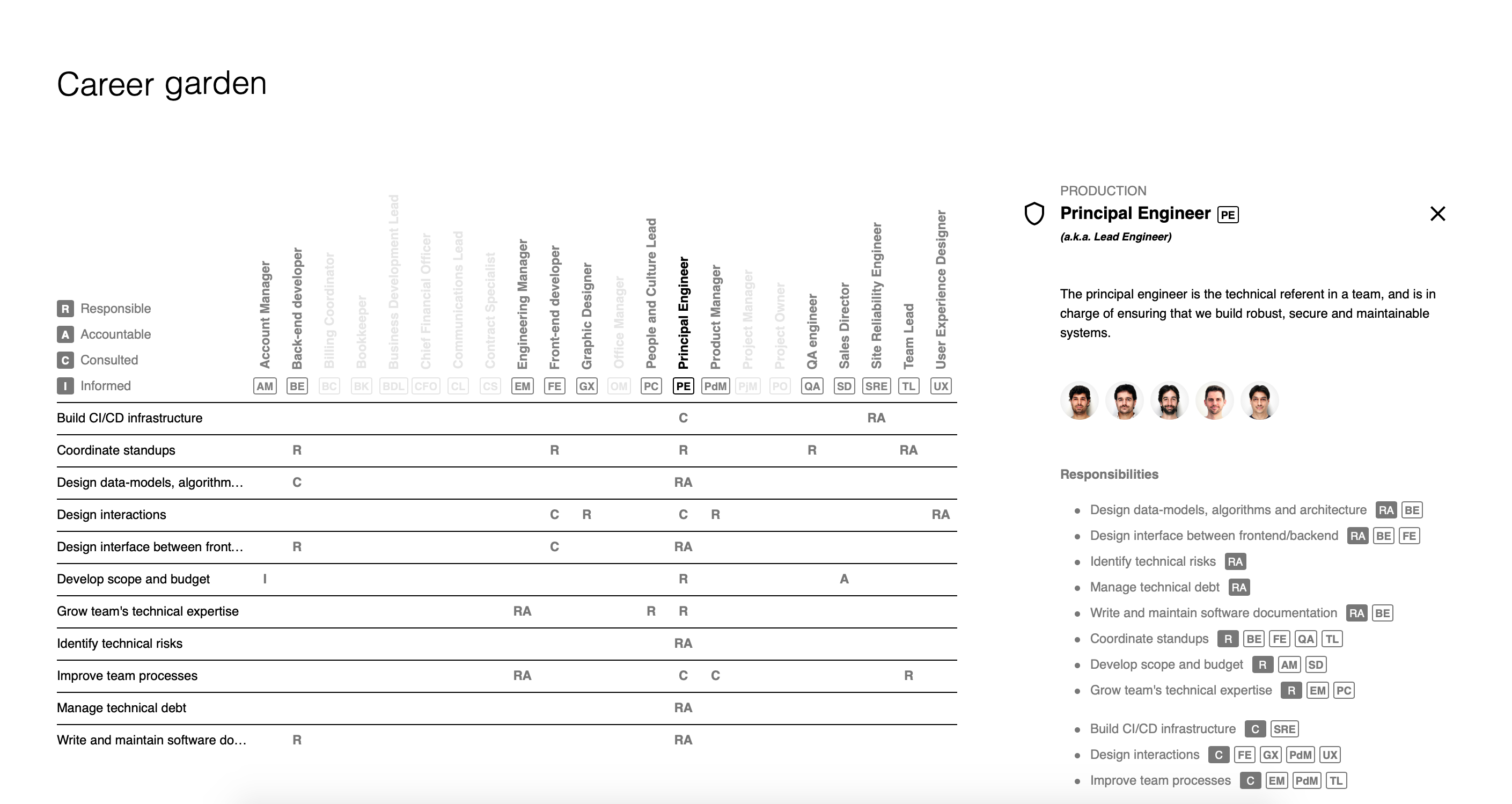

Being such big fans of UX, we couldn’t help but build a beautiful UI for our garden, and not only it looks slick, but you can also click on everything, and see how it all connects. We’re still on the fence about actually making the UI look like a garden, so stay tuned for further developments.

In this example, we’re viewing the Principal Engineer, and in addition to the role’s description and responsibilities on the right, we see who carries out that role in the organization, and on the left we can see how each responsibility encompasses interactions with other roles. At the same time, there are several dimensions to each role, related to the degree of involvement each person has with that role and its associated responsibilities: some are responsible for the actual execution, some are accountable for making that execution take place, others need to be consulted about the decisions involved in the execution, and others yet only need to be informed, just kept in the loop. For those of you out there with a smirk and a raised eyebrow, yes, this is what is known as a RACI matrix (you knew this, right?).

This intentional intertwining of roles contributes several cool features to the model: first, over the years we’ve learned that both workers and clients benefit from a regular practice of bouncing ideas, and in a garden where paths often cross, you get a lot of that; second, it allows everyone in the organization the possibility to take vacations or days off, without leaving their responsibilities unattended; third, multiple levels of involvement and accountability make the end result much richer, whether you’re dealing with software, culture, making a movie or opening your own restaurant. There’s really no need to delve into the benefits of collaboration, so we won’t do it here. But a very cool feature of this system that we will mention is that it strengthens personal relationships within the organization. Particularly, since we already have mechanisms in place that contribute to a strong collaboration within our team.

Work at Manas is not only focused on the outputs, like delivery to our clients, although a great deal of our attention is put there; it is also very much aware of what goes on inside, since we believe that improving what goes on inside our organization inevitably and dramatically improves what comes out. It is a work in progress, and many iterations are sure to come in the future, but we are convinced that the best approach to solving an interesting problem is turning that interest into action. We’ll keep you posted.