The names Robertson, Allen, Parker, Philips and Goodwin may not mean anything to you, but they all played a part in building the world you live in.

No, they’re not the members of some 70s band that inspired any sort of social or musical movement, and they’re also not a band of infamous robbers that pulled off some big heist back in their day.

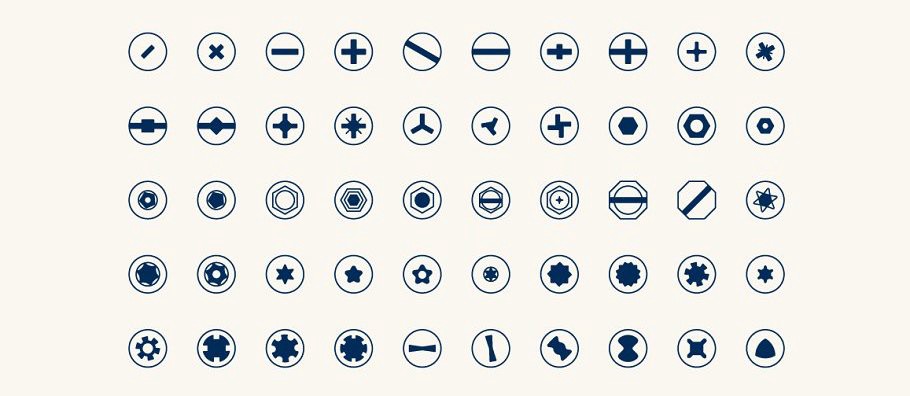

They are, first of all, not a group. And this isn’t even the entire list of names. There are several more people involved, and none of them even worked together. In fact, they were all competitors. Competing on what? On who created the most successful… drumroll, please… screwdriver!

A bit of history

Some consider that the screw thread was invented around 400 BCE by a man named Archytas of Tarentum. Regardless of its inventor, and the date and place of birth of the screw, it is known that by the first century CE, screws were already a common thing, and they were used in everyday things like wine presses, olive oil presses, and for pressing clothes. But it took fifteen centuries to go from that to our modern day metal screws, and it wasn’t until 1798 that David Wilkinson invented machinery for the mass production of threaded metal screws.

Today, with the exception of a handful of manufacturers that use proprietary screw heads to discourage users from tampering with their products, we mostly use a combination of Phillips and flathead screws. For decades, though, the story was substantially different. Throughout the 20th century, there was a battle of sorts where inventors and manufacturers raced to become the ultimate standard in screw heads.

This made a lot of sense because there was a lot to be gained –or lost. If you specialized in manufacturing one of these screw heads and large appliance manufacturers chose that screw head for every product they made, you had a booming market to tend to. On the other hand, if those manufacturers went with another screw head, you were suddenly stuck with a bunch of screws that no one wanted to buy. Talk about being screwed!

A similar thing happened not too long ago, in the early 2000s, with cell phone chargers: every cell phone –and charger– came with its own connector, and sometimes the same manufacturer used more than one type, and it varied from one device to another.

That madness lasted up until 2009, when the European Commission launched an initiative that resulted in the specification of a common external power supply (EPS). According to the European Commission, a common external power supply (“charger”) standard was desirable because,

“Incompatibility of chargers for mobile phones is a major environmental problem and an inconvenience for users across the EU. Currently specific chargers are sold together with specific mobile phones. A user who wants to change his/her mobile phone must usually acquire a new charger and dispose of the current one, even if this is in perfect condition. This unnecessarily generates important amounts of electronic waste. Harmonising mobile phone chargers will bring significant economic and environmental benefits. Consumers will not need to buy a new charger together with every mobile phone.”

The struggles of compatibility have long been a part of modern human history. Some of them we’ve settled, but some still live among us:

“In metric, one milliliter of water occupies one cubic centimeter, weighs one gram, and requires one calorie of energy to heat up by one degree centigrade — which is one percent of the difference between its freezing point and its boiling point. An amount of hydrogen weighing the same amount has exactly one mole of atoms in it. Whereas in the American system, the answer to ‘How much energy does it take to boil a room-temperature gallon of water?’ is ‘Go f•ck yourself,’ because you can’t directly relate any of those quantities.”

The problem behind it

At Manas, we often find our way to making a joke about wanting to let every programming language go, and simply program everything in Excel. I mean, even grandmas are using it to create knitting patterns!

It’s a joke, of course, but it is also telling: software development has evolved into an enormous field, with so many different options as to languages, frameworks and tools, that keeping up is a job in and of itself.

That is when standards start to look attractive. Why keep a toolbox filled to its brim with ten different types of screwdrivers, in a variety of sizes, when you could simply carry a nice set of “the standard ones”?

The problem is that not everything can be thought of as a screwdriver.

On one end of the spectrum, we have the reinvention of the wheel on a daily basis: inventing a new screw head for each new thing we need to fasten. On the opposite end of the spectrum, there is the proverbial hammer that makes every problem start to look like a nail.

So, even though using only Excel to program would be totally impracticable, there is also a point in considering how many languages, frameworks and tools is practical to have under one’s belt. After all, a jack of all trades is a master of none.

What we need, then, is some sort of guide that helps us calibrate our efforts when trying to solve problems using technology.

Build, buy or adapt… that is the question

There are three ways to approach problem-solving with the use of technology: you can build something from scratch, you can buy something off-the-shelf or you can adapt an existing solution (either off-the-shelf or previously built within your organization) to address new needs.

It is important to note that these three approaches are not isolated buckets, but part of a continuum that goes from generic commercial software solutions targeted to large markets, all the way to custom software built specifically for use cases.

Let’s take closer look to each component, following this continuum:

1. Buy

Off-the-shelf standardized software solutions work great for tending to needs that are transversal to your business. These are needs that are likely not a core element of the specific design of your operation; they are necessary, but not a central element of what your company does.

Therefore, it’s probable that other organizations have similar versions of these needs, and the solution allows for a fair amount of standardization. However,

“The more reusable something is, the less usable it is.”

— Neal Ford

Examples of these transversal needs in organizations are Project planning and management, Project accounting, Data collection, Dashboards and metrics, Monitoring & Evaluation, Statistical analysis, Team communication tools, etc.

Almost every organization has to find a way to cater to these types of needs, so it’s fair to assume that a significant amount of thinking has gone into sound ways of solving them. It doesn’t make too much sense to spend your time reinventing this wheel, unless you have a really good reason to justify building a custom set of wheels for your company.

The level of standardization of these needs allows for a quick checklist of what to have in mind when choosing one of these tools:

- Data portability

- Interoperability

- Contract type

- Platform support: Windows/Mac, Mobile (iOS/Android), Tablets

- Privacy and security

2. Adapt

Half-way between building and buying, the approach is to buy an off-the-shelf solution and adapt it to your needs. While buying a packaged solution requires no development and little in the ways of implementation, it yields reduced customization. Adapting a tool makes for a better fit between the problem and the solution, at the cost of some degree of work on top of a base state of the tool, while still not requiring a full-blown development effort.

These adaptations usually come in three major forms:

- Plug-ins: widespread platforms like WordPress, Moodle or Slack offer a great deal of functionality as-is, but there is also a wide selection of plug-ins to customize the tool to more specific needs, and you can also develop your own.

- APIs: a lot of platforms like Google Maps or PayPal out there allow you to integrate via their APIs and consume some of their services, allowing you to add functionality to your system without having to develop it.

- OpenSource: these days, for most standard problems, free and open-source libraries are available, that can save a lot of time and effort, and help you avoid vendor lock-in.

3. Build

Finally, there are scenarios where it makes the most sense to build a solution from scratch. It might be because you work in a niche space, sufficiently small that no one has developed a one-size-fits-all solution, or the available options are not cost-effective. In these cases, building is not only the best option, it is also the only one that makes sense in terms of TCO.

Another scenario where building is the best strategy is when you set out to disrupt a space, either by re-thinking how a service is delivered or how a process is done. In this case, your product needs to bring a significant enough degree of innovation to cast a shadow over every other packaged solution.

For these types of endeavours, the cost (both in time and money) of adapting generic products to something useful and groundbreaking is so large that the best course of action –and the only one that makes any sense– is to simply start fresh.

For these kinds of aggressive innovations, which aim to create a considerable distance (or moat) with regards to the competition and other readily available solutions, you will need to build a custom software solution that supports your business vision.

Another scenario where it makes sense to build a custom solution is when the tool or solution will be core to your business for a long time: you don’t want to depend on external providers for services that will be at the center of how you operate. They might change their policies, jack-up their prices, update their APIs or even go bankrupt, and where does that leave you?

Driving the point home

So, what can we take home from all of this talking about screwdrivers, cell phone chargers and pictures of hermit crabs?

Standardization may very well be the standard, but innovation occurs at the fringes.

Knowing when to buy, adapt or build is key to find a balance between making an efficient use of your resources and creating value that puts your business ahead of the competition. It all boils down to 5 essential questions:

- Is this need core or transversal? Identify how far or how close this need is regarding your core business to assess how you will invest in solving it.

- What are the available options? Review existing solutions in the market and verify criteria (find or create your own checklists).

- What is the Total Cost of Ownership? Everywhere on the Internet there are formulas for calculating TCO. This is one of them.

- Is this cost-efficient? Either building something too similar to an existing household brand or buying something ready-made that only covers a very small portion of your needs can be a bad idea. Make sure you do the math and confirm cost efficiency before setting a course of action.

- Is this still working out? Last but definitely not least, review periodically if the choice you made back when, in a different context and with different information, still holds water in new contexts, with new information.

So, after this long and winding ride, you should be better prepared to decide how to approach problems with technology. This is not an exhaustive guide to do so, but it is a pretty good place to start. Hope it helped!